Josh MacIvor-Andersen is a nationally award-winning storyteller with publications ranging from the purely journalistic to the experimentally lyric. His essays and reportage have been featured in The Guardian, The Paris Review Daily, Gulf Coast, National Geographic/Glimpse, and many other journals and magazines. He is a lifelong intrepid traveller driven by curiosity, beauty, and appetite.

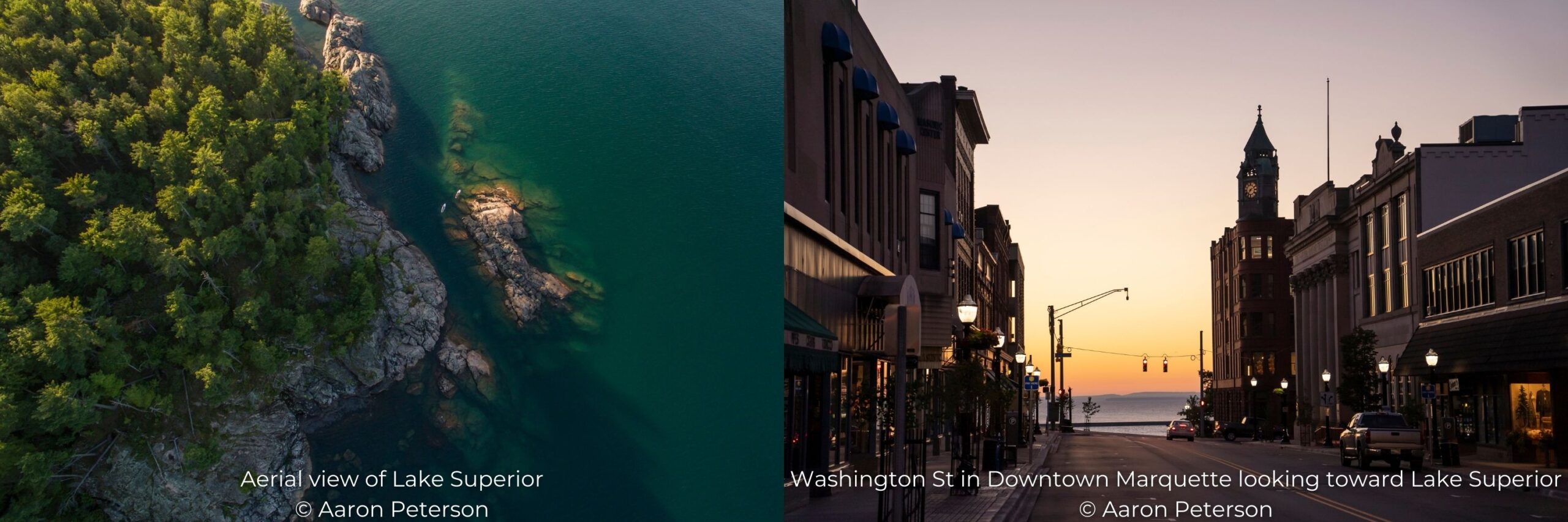

Twice a year in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, in the small, bustling, lake-side city of Marquette, the early morning sun peeks over the horizon only to be perfectly framed at the centre of downtown’s decommissioned ore dock, that almost gothic monolith of steel and concrete whose throat, for a few brief minutes each November, catches fire.

The locals call it “Orehenge”; something mythic, sacred, perhaps even magical—another bit of blistering evidence that this place is, indeed, special.

The thing is, though, a thousand years before 1931 and the construction of the ore dock ever began, the sacredness of this place was already well assumed.

“It’s all part of a big system that helps us live,” says Jason Quigno, a Michigan-based Anishinaabe sculptor whose work transforms slabs of raw rock into flowing vestiges of animals in flight, the exultant movement of water and flame, and the stories and images of his ancestors. “The dirt, the earth, the soil that grows the trees, the trees that filter the air; that’s what makes all that stuff sacred. It sustains us.”

Quigno’s newest installation, “Seven Grandfather Teachings,” will live in a large semi-circle adjacent to the ore dock and captures some of the core tenets of Anishinaabe teachings: love, respect, bravery, truth, honesty, humility, and wisdom. Yes, seven. And each teaching will emerge from locally sourced stone in a different abstract shape, and at the circle’s centre, eventually, the 10-foot-tall “Ishkode,” a curving fire sculpture erupting from the ground, flickering in solid rock toward the sky.

“The Seven Teachings are ancient—they’ve been around for thousands of years—but they’re for everybody,” says Quigno, who hopes for all his art to evoke strong feelings in his viewers. “Some people might be moved by the shape of a certain stone, or they see something with their eyes that translates to a certain feeling. It’s a place for people to come and sit and contemplate.”

The “Seven Grandfather Teachings” installation will live not just in a physical place where the shores of Lake Superior intersect with the town and terra firma, but also within the larger ideological, philosophical, perhaps even theological question of: What the heck do you do with a seven-mile stretch of prime lakeshore real estate?

The environmentalists have a simple-yet-passionate answer, as do the developers.

Thankfully, Marquette was spared those heated conversations due to the vision and groundwork already laid by its Arts and Culture office, whose proposed trail project would soon bring alive the unique heritage, history, and physical environment of this place through public art, interpretive signage, and innovative design alongside an extensive trail system that, unlike many sea-side destinations, is already in place. The big win came when grant money ensured indigenous art as the trail’s centrepiece, its anchor.

“The story is already there,” says Tiina Morin, the city’s Arts and Culture Manager, who emphasizes how rare it is for a city to have as much public access to the shoreline as Marquette. “And there are multiple stories: pre-indigenous history, the history of the almost ten Anishinaabe villages that once lined the shoreline; it’s the industrial history where everything was polluted, and now this whole new history of cleaning it all up and making it usable for the community—the greening of it.”

The Cultural Trail initiative will interpret those story braids along a decades-old multi-use trail, with emphasis on multi. Regular usage includes pure ambulatory pedestrianism, battery-boosted e-cycling, ordinary old-school pedalling, and even the clickety-clack of hard-core cross-country skiers training in the off-season on long in-line skates with rubber-tipped poles. In other words, the Cultural Trail’s storyline can be observed and absorbed at almost any speed.

“My hope with these interpretive sites is to give us a different way of looking at our shoreline,” says Morin. “A different perspective. Creating spaces for our community to come together, to tell our history and connect—past, present, and future.”

Marquette, Michigan–what the Anishinaabeg people have called Gichi-namebini Ziibing since forever–has always exuded a sacredness of place, the profundity of a geographic and human history rooted in sand and soil, in industry and conservation—and all of it markedly lakeside.

The artists (as they tend to do) have always been there to capture it.

“There are a lot of artists in Marquette who tap into the spirit of place,” says local found-object-artist Stella Larkin, who incorporates fibres, plastics, driftwood, and even bottle caps into her sculptures. “It’s atmospheric. It’s vibrational. It’s something you feel in the presence of the lake or when you’re in the woods.”

Larkin pays attention. She walks the paths, the beaches, the switch-back trails through the forests, and everywhere she looks she finds gifts. From the universe. The muse. Objects—both natural and human-made—asking to be transformed into art.

“All my art is driven by destiny, fate, and serendipity,” says Larkin. “Anyone can go to a big box store and buy anything, of course, but if something presents itself on the sidewalk, I take it as a sign—the universe telling me to use these things.”

Even after the storms wash over the pristine shores of Lake Superior, Larkin doesn’t see trash and debris, but artistic potential. She collects that bounty, everything from hair combs to pine cones to plastic beach toys forgotten by children and suctioned out to sea, only to be washed back to the artists’ hands. Larkin weaves a fragmented tapestry of found objects into a single, profound, cohesive whole.

“When you find things, you start wondering where it’s been or where it came from; everything has its own amazing history,” says Larkin, whose gallery, Rustico, lives just off the lake-side trail where Quigno’s installation will soon break ground. “It’s for me to decide what to do with that; it’s faith and serendipity and having this openness to inspiration.”

Lots of things make a place attractive to tourists and travellers. Marquette has many of them in spades, including a rugged freshwater coastline remote enough to feel as if it’s all for you, a unique local food scene sourced from the hard work of creative and gritty farmers just outside of town, and a tangled web of world-class mountain bike trails unspooling directly from the city’s doorstep.

The city’s arts and culture bring it all alive—the unique expression of folks determined to translate abstractions like place and spirit into tactile and visual art that transcends even the walls of a museum or gallery.

“From an artistic perspective, a cultural perspective, there’s something really exciting happening across the Upper Peninsula, but especially in Marquette,” says Morin, who feels like her city is in the throes of another great renaissance—one built on conservation and stewardship, carrying forward the commission of its original Anishinaabe inhabitants. “We’re at another precipice, another moment—lots of exciting discussion about our future, yet there’s this huge push to take care of our land, be responsible, be thoughtful about how we move forward, and I think the arts are a huge part of that.”

Feeling inspired? Experience the magic for yourself by booking one of our Sustainable Journeys.

Editorial submission – 03rd January 2023