By Luke Waterson

‘Everybody is connected to nature in Finland because everything is,’ Antti Harkonen, founder of a kayaking and adventure travel outfit says as he shows me where some of Scandinavia’s finest city kayaking routes kick off at Tampere’s Soutukeskus Venesatama (Rowing Centre). While the view north is towards the tree-flanked skyline of the country’s second city, the panorama west pans out to Pyhäjärvi – one of the two vast snaking lakes bounding Tampere and a scene of island-flecked cobalt waters, conifer-clad shores and emptiness that seems to be Finland’s de facto late-summer vista whichever way you venture.

‘Water, forest, mountains, fire…’ it’s in the genes of us Finns. We have enshrined in law the jokaisenoikeus, the Everyone’s Right or Freedom to Roam and it’s in our DNA more than anywhere else in the world I know. Everything we are famous for has to do with nature: swimming in the lake after a sauna, cross-country skiing, hiking, fishing, kayak-camping, and being out overnight in the wild which is extra harmony. And most of it is water-based because we have so much water.

Finland’s geographical statistics make mighty impressive reading, especially if escaping the daily grind of civilisation is your thing. Population density averages out at about 18 people per square km, dwindling to just two souls per square km in Lapland. Terra firma here is 73% forested, giving the nation more tree coverage than anywhere else in Europe. And oh, those lakes: around 188,000, according to most estimates, meaning Finland boasts almost twice as many bodies of water as the continent’s second-most lake-blessed land, Sweden.

‘Finland has to be one of Europe’s – maybe the world’s – best kayaking destinations,’ Harkonen enthuses. In Tampere you can quickly walk from the city centre to the lakeshore, start paddling and be alone with the water birds in under 1km. Then we have Kolovesi National Park, where I often run kayak trips: park access is solely by water, and most people get there by kayak. Another of my favourites is Archipelago National Park in Southwest Finland, with more islands in one area than anywhere else on Earth. It’s great because tourists are coming to Finland with kayaking as an agenda, and when we do this activity we’re travelling with no noise, not polluting anything, and no disruption to nature. Recently in Kolovesi, my group and I got so close to one of the world’s rarest seals, the Saimaa ringed seal, surfacing right alongside me.’

East in Nuuksio National Park, the easiest protected tract of nature in Finland to access for overseas visitors at just 30 km from Helsinki Airport, further eclectic encounters of the wild kind await. I can even board a Helsinki Metropolitan Area bus out to the park, a surprisingly wild old-growth forest given its proximity to the capital, splayed out around gangly lake Nuuksion Pitkäjärvi and one of Europe’s last two bastions of the Siberian Flying Squirrel. Here I meet Teemu Tuomarla, CEO and founder of the park’s lodge, fittingly named after the elfin guardian of the Earth in Finnish mythology. Completely wind-powered and aiming to achieve carbon-neutral status by 2025, the lodging not only provides the sustainably-minded with a conscience-free stay but lets its guests proactively participate in habitat regeneration through a partnership with the park authority and the nearby nature centre through ‘Planet-Positive Conservation Holidays’.

‘Tourists engage in invasive species management, where they learn about the delicate balance of ecosystems and reducing biodiversity, and undertake guided removal efforts of alien plants like lupine which, whilst visually appealing, pose a threat to local flora,’ explains Tuomarla. ‘They can also help with meadow restoration and deepen their understanding of the local environment through our educational workshops. The goal is to foster a deeper connection between people and nature. Our visitors not only enjoy the beauty of Nuuksio National Park but also contribute to its preservation and enhancement.’

Tuomarla hopes that the park’s 2023 trialling of Planet-Positive Conservation Holidays is adopted countrywide, as the spotlight shines on Finland in the race towards achieving the world’s first carbon-neutral society. Copenhagen (2025) leads the pack in terms of cities, but six Finnish cities – Helsinki, Espoo, Tampere, Turku, Lahti and Lappeenranta – are striving for carbon neutrality by 2030, a number eclipsed only by Sweden, and new Prime Minister Petteri Orpo has reaffirmed Finland’s commitment to becoming the planet’s first carbon-free nation by 2035.

Excited to explore the Finnish Lake District for yourself? On this 15-day trip, you’ll explore the must-see attractions of Helsinki, the Lake District, and Tampere. You’ll stay in sustainable accommodation and discover Olavinlinna Castle, enjoy a photography trip on Lake Saimaa, and experience the hip attractions of Tampere.

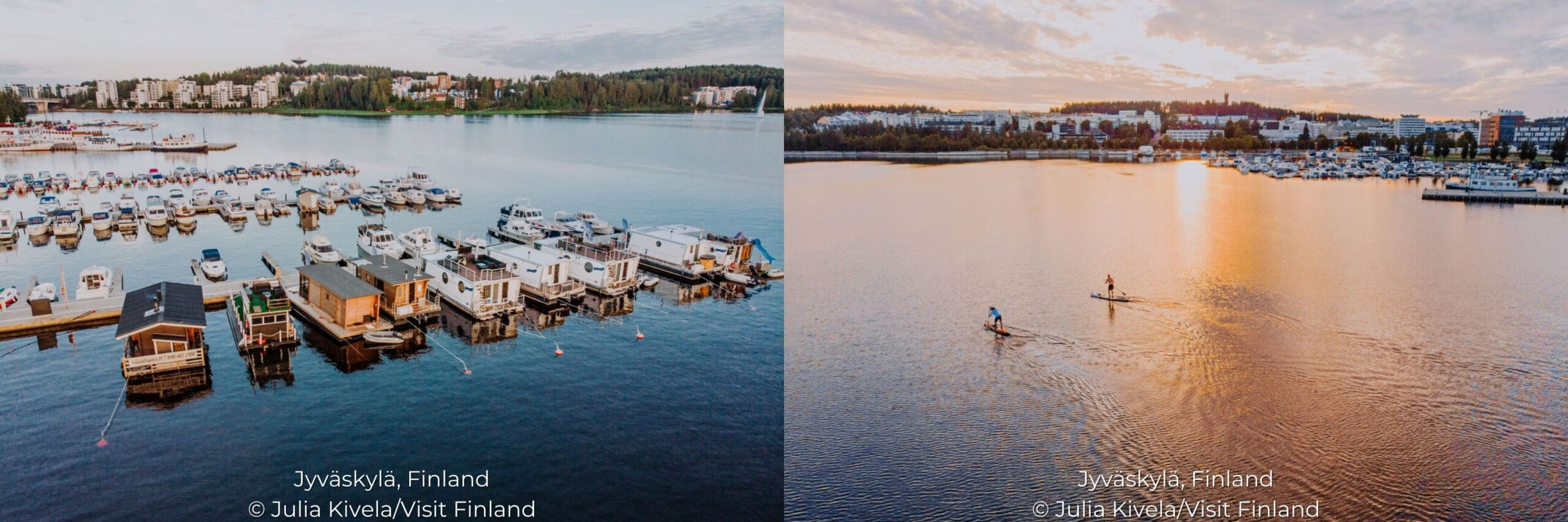

While even demarcating Finnish Lakeland as a region is a little like designating a jungle zone within the Amazon Basin, this especially aqueous area spanning from Lappeenranta in the south to Kuopio in the north is, as one of Finland’s most talismanic postcard-perfect landscapes, another major focus for sustainable tourism.

In the south of Jyväskylä municipality, I take the bus out across a tree-lined causeway to Säynätsalo, one of several road-linked islands in Päijänne, the country’s second-largest lake. Säynätsalo Town Hall, designed by famous former Finnish architect Alvar Aalto and one of his many architectural icons in the vicinity, has been repurposed as an innovative private enterprise acting as a showcase for Aalto’s work and a nexus for ecological regional visitor activities. Tavolo Bianco Oy was established to benefit the community and facilitate the rejuvenation of the Lakeland ecosystem.

‘I like to talk about transformative travel,’ explains founder Harri Taskinen. ‘It’s sustainable travel that doesn’t just preserve what we have but tries to improve it. Visitors are guided in moving with low emissions, pointed towards ecological services like nature trips and advised how to sort rubbish. We don’t believe in fenced areas for tourists here.’

Taskinen acquired extensive experience in transformative tourism, summarised in his words as ‘a need for skilled and competent staff to improve living environment’ through volunteer work in India’s slums. He had long contemplated how to transfer the model to Finland.

‘To start with,’ says Taskinen, ‘the building that is the hub of our operations is a great model. We can learn from Aalto’s architecture and incorporate it into a way of life. The harmonious interaction of man and the environment emphasized by Aalto can also be a way of life for modern-day locals and tourists visiting these islands. In 2023, we started offering our volunteering project. Volunteers can participate in running the premises, developing positive travel experiences, guiding visitors, and getting to know the people who form the active community in Säynätsalo. It causes at least a small change.’

The road winds a little further after Säynätsalo: out to Muuratsalo island and the Muuratsalo Experimental House, also designed by Aalto: indeed, it became his summer residence for many years. Wedged between forest and craggy shore, for Aalto it was also a place to hone and broaden his creativity through the use of new materials and the development of ideas.

‘Muuratsalo is intended to serve as a peaceful architect’s studio and an experimental centre suitable for carrying out experiments that are not yet ready for other environments. It is also to be a place where the proximity to nature provides inspiration…’ the architect would comment in 1953.

To me, it seems what Taskinen is doing with transformative travel around Päijänne today has the perfect backstory in the ethos of Aalto, the area’s most famous resident.

Seven hours north by train is Rovaniemi, the capital of the Finnish Arctic. It is best known for the glitzy razzmatazz of Santa Claus Village, but locals emphasise that here, perhaps more than anywhere else in Finland, is the cockpit of the drive towards more sustainable travel.

‘Nature is everything to us,’ says Marja Mäenpää, marketing director of Arctic Snow Hotel, which is a land celebrated for its thick snow cover has to be among Lapland’s greenest accommodations given that it is constructed solely from snow and ice. ‘If we don’t take care of it, we don’t have our business – or much at all. The only way to work in these fragile Arctic conditions is to do it in a sustainable way.

‘One of the company’s owners, Ville Haavikko, was actually studying snow construction when the idea to build a hotel from snow was born. Ours is probably the largest snow hotel in Northern Europe. We rebuild each year. We gather snow from the previous snow hotel and store it under large tarps: around 50% lasts to use as the foundation for next year’s hotel. Then we take water from Lehtojärvi Lake by the hotel to make the rest of the snow needed. The snow melts back into the lake: it’s one-of-a-kind recycling! We are even able to use ice for the furniture that is stored in solar-heated warehouses throughout the year.’

‘For me personally, Finland’s commitment to greener travel makes me feel relieved,’ reflects Rovaniemi resident and Head of Sustainable Development for Visit Finland Lisa Kokkarinen. ‘Climate change is a threat to humanity. It feels good to be part of the fight against that.’

Glossary

Jokaisenoikeus: Everyone’s Right, the more gender-neutral version of jokamiehenoikeus (Everyman’s Right), a form of the Freedom to Roam rights enjoyed across several European countries and permitting public access to both publicly- and privately-owned land for purposes of recreation.

Feeling inspired? Experience the magic for yourself by booking one of our Sustainable Journeys.

Editorial submission – 07th March 2024