Josh MacIvor-Andersen is a nationally award-winning storyteller with publications ranging from the purely journalistic to the experimentally lyric. His essays and reportage have been featured in The Guardian, The Paris Review Daily, Gulf Coast, National Geographic/Glimpse, and many other journals and magazines. He is a life-long traveller driven by curiosity, beauty, and appetite.

Let’s not start talking about Marquette, Michigan’s robust, innovative farm-to-table scene without first establishing a shared lexicon—we need to pin down words like tenacity, grit, and maybe even gumption.

This is the language that captures what it’s like to stare down a growing season strangled by epic winters, the supply chain challenges of living three hours off the nearest interstate, and still have the farmer’s audacity to say: Yep, I’m going to grow some kale for profit, or the chef’s courage to say, I’m going to source from my neighbours instead of what ships in cheap and consistent from Chicago.

Gumption indeed.

“The norm is not necessarily the best path,” says Alex Palzewicz, the executive chef of an experimental kitchen housed within the Barrel and Beam brewery on the outskirts of town. “We can be a more thoughtful business—it’s challenging, but it’s the passion behind what we do.”

Palzewicz is quick to delineate her approach in the kitchen from a more traditional one, where the menu always comes first. Once the dishes are decided, according to that model, the chef simply places the order.

Palzewicz flips the culinary script, searching out ingredients readily harvested among a string of nearby and regional farms, and builds her recipes from that abundance.

“I’m not looking up recipes and making the food fit,” she says. “I’m driven around what’s available. It might be harder to go in a different direction, but I think it’s a better experience in the end.”

Here’s the big secret, though; despite the remoteness of place and the challenge of a winter-choked growing season, there is a ton of availability. Michigan, it turns out, is neck and neck with California in terms of diversity of crops. Many of the other states? Long ago fallen to corporate and federally funded mono-crops like soy and corn.

“The opportunity is real here,” says Nick VanCourt, founder and head brewer of Barrel and Beam. “We can do this because these things are available to us.”

Cue the cherries for the brewery’s Spooky Kreik, a flemish-style sour, sourced from the fingertips of Michigan’s mitten. Cue the hops and barley delivered directly from the mitten’s thumb. Cue even the local flour used to make house crackers when mixed with the left-over, post-brewed grains.

Sustainability, after all, is not just about where you buy stuff, but also what you do with the waste.

“What I’m doing would not be possible without creative freedom,” says Palzewicz, who credits VanCourt with supporting her vision, as well as her commitment to utilizing localized ingredients from the region. “We are called a test kitchen because we are a creative space that understands how our food systems need to change.”

The historical brackets that frame most local food scenes are typically pretty wide. Yes, Barrel and Beam’s history is rooted in the tenacity of its founders, VanCourt and his partner, Marina Dupler, who in 2016 set the compass needle of their business opposite of the status quo. But also in gritty entrepreneurs, Fred and Emma Klumb, who first built the building in 1934, in the midst of the Great Depression, determined to launch a supper club.

The Klumbs project lasted until 2007.

But Marquette’s brackets go back even further, all the way to the smattering of Anishinaabe communities that once populated the shoreline, where manoomin (wild rice), game, and of course fresh water were abundant.

Some towns do a pretty good job of reducing that rich history to a roadside plaque or two, but Marquette continues to celebrate and enliven its indigenous history in its art and installations, cultural events, and even in its modern-day food scene.

“One of the interesting threads in this area is the indigenous component,” says Phil Britton, principle of Fresh Systems LLC, a consultancy working within local food systems. “That’s where the energy is right now, in how those foods are being used and resurfaced.”

What he means is that manoomin—the food source that was once the cause of ongoing migration patterns among indigenous communities—has recently been christened by Michigan’s governor as the state’s official grain. What he means is that cooking classes offered through Marquette’s community-owned food co-op are now using indigenous recipes and ingredients to illuminate not only the food but the intricate, rich histories connected to it. And what he means is that food sovereignty symposiums that centre indigenous ingredients, approaches, and farming are taking over the local university, yes, but also the kitchens of some of the town’s most prominent restaurants.

“Local food movements and farm-to-table is not new,” says Britton. “But there are some cool ways indigenous food is being used and brought to the forefront. And just from the acknowledgement standpoint—that the people who were here before us were able to live, survive, and thrive in this area using these traditional foods—the honouring and elevating of that is important.”

To live. To survive. To thrive. Before the buildings and roads. Before the electric grids and push-button everything. A sustainable and nourishing abundance of protein and grain, fresh water and minerals.

And it’s all still here.

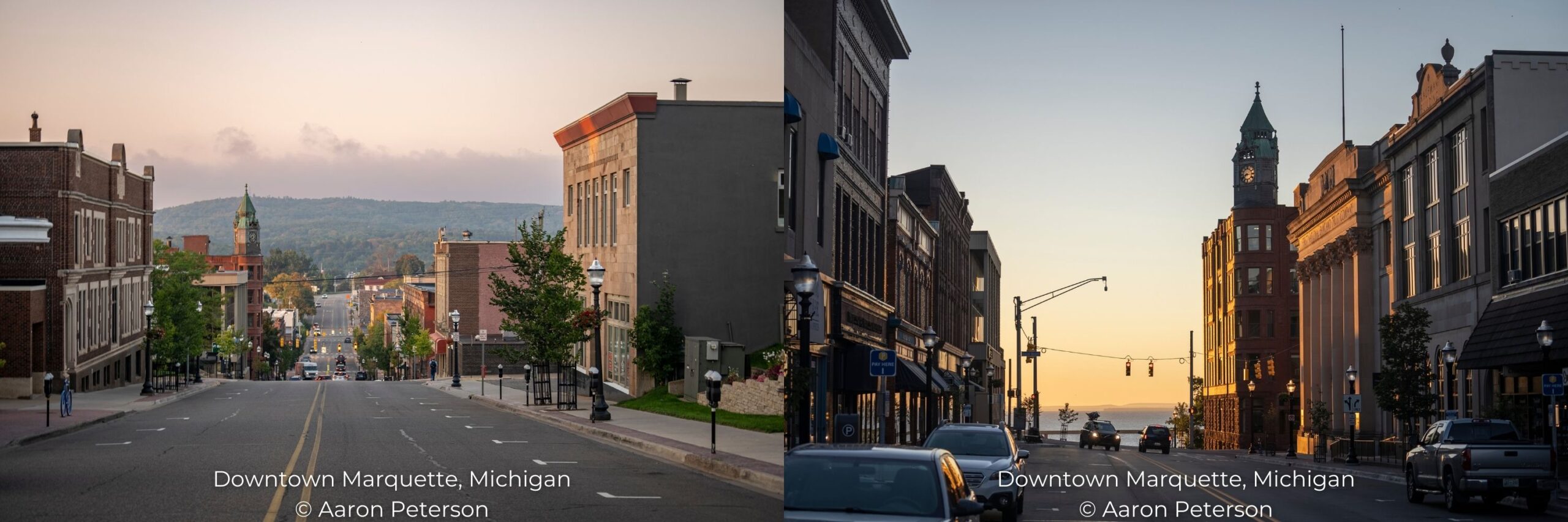

Interestingly, as Marquette developed into the vibrant modern city it is today, the BIG traffic (all those cars, trucks, and semis barrelling along Highway 41) was funnelled west before ever hitting downtown. Along that heavily trafficked corridor is where most of the franchises and chains blossomed, their brightly lit corporate logos recognizable from afar.

That means that Marquette’s historic, bustling downtown is populated almost exclusively by locally owned restaurants, cafes, and breweries, many of which are committed to sourcing their ingredients from nearby and Michigan-based producers.

So when National Geographic swoops into town for a special feature, documenting a day in the area through photographs and slick drone footage, they train their lenses of course on the incredible natural beauty of the area—the lakeshore, the mountains, the brilliant fall foliage—but also on downtown businesses like Bodega, whose owners, Amber Johnston and Libby Nelson, have built a menu based on the relationships they’ve made with a who’s who of local farmers and producers committed to sustainable practices.

The difference, they argue, is palpable, tasteable. Of all the burgers in town, for example, Johnston and Nelson claim that the clean water and sweet grass of their beef supplier, Superior Home Farms, makes theirs the stand-out winner in a VERY crowded market.

The truth is, almost every block of Marquette’s compact and colourful downtown is anchored by the entrepreneurial vision of someone who has chosen to make this place home, and in turn provide services or goods for its local residents. Boba tea and independent bookstores, art galleries and crepes, and really, really good beverages (hot, cold, fermented or non).

Just a few blocks down the 3rd Street hill from Bodega, on Washington, a triumvirate of sustainably-minded businesses are lined up in a row — retail, chocolate and food, an upscale bistro purpose-built into the old Delft cinema—all three equally committed to anchoring profit with principle.

“We’ve always believed that doing good business is taking care of the culture we’ve created, where we prioritize our employees and the community and the environmental impact we have,” says Jen

Ray, co-founder along with Tom Vear of all three businesses, and a key advocate for moving the whole shebang toward B-corp status. “It’s not a comparison, but more how can we all move forward while doing what we can within our own situation.”

Ray recognizes the privilege of saying no to styrofoam packaging and yes to compostable candy wrappers. She knows not every business can afford to slap solar panels on the roof, but she believes the community-wide conversation of “how we do business, how we do development more sustainably” is a substantial part of Marquette’s entrepreneurial DNA and steering the whole town toward a uniquely bright future.

Barrel and Beam’s Alex Palzewicz—who returned to town after a culinary sojourn in Seattle—agrees.

“There are a lot of exciting things happening around food in our area,” she says. “I’m very optimistic.”

Feeling inspired? Experience the magic for yourself by booking one of our Sustainable Journeys.

Editorial submission – 4th January 2024